Casa Pia: The Making of a Modern European Witch Hunt

by RICHARD WEBSTER

……………………………………………

www.richardwebster.net

8 December 2010

……………………………………………

ON FRIDAY 3 SEPTEMBER IN LISBON, after a trial lasting almost six years, six defendants were found guilty of sexually abusing thirty-two teenage boys who were once residents of Portugal’s state-run network of vocational schools, Casa Pia — or the Houses of Piety. According to the report which appeared in The Guardian the next day, the verdicts ‘exposed the truth of more than three decades of rumours about systematic abuse of young boys at the 230-year-old Casa Pia network of orphanages’.

When, amidst massive security, the judges in the court in Lisbon read out the verdicts, the main defendant in the case, Carlos Silvino, who had faced more than six hundred charges of sexually abusing or raping all 32 teenage boys involved in the case, was sentenced to eighteen years imprisonment. Silvino is a former resident of the schools, who had subsequently been employed by the Casa Pia network as a driver. According to the version of the case presented by most Portuguese journalists, he had been the central figure in a paedophile ring which supplied adolescent boys from the schools to be sexually abused by well-known professionals and celebrities.

TV presenter Carlos Cruz at the beginning of the trial, 2004

Although only a small proportion of the famous people who had been named during the course of the case were ultimately prosecuted, Silvino’s co-defendants included one of Portugal’s best-known television presenters, Carlos Cruz. Beside him in the dock were Jorge Ritto, a career diplomat and former UNESCO ambassador, lawyer Hugo Marçal, a doctor, Joao Ferreira Diniz, and the former deputy principal of one of the homes, Manuel Abrantes. These five defendants were charged in relation to seven of the 32 alleged victims and received sentences of between five and seven years. A seventh defendant, 68-year-old Gertrudes Nunes, who had supposedly provided her house as the venue for abuse, was acquitted.

‘A monstrous judicial mistake’

For the newspapers which reported the story in the UK, there seemed to be little doubt that a sinister conspiracy had been exposed and its leading members finally brought to justice. The evil nature of this supposed conspiracy was heightened by the manner in which journalists persistently described a network of state-run vocational schools for young people up to the age of 18 (many from broken homes) as ‘orphanages’.

‘To most people’, wrote Jerome Taylor in The Independent, ‘Portugal’s state-run orphanages seemed like a safe haven for thousands of children who had been robbed of their parents . . . But for an elite paedophile ring, which included a former ambassador and a prominent television celebrity, Casa Pia orphanages were something entirely different. They were supermarkets stocked with children to abuse.’

To many observers in Portugal as well the guilty verdicts seemed to bring to a conclusion a massive scandal. The Casa Pia case has gripped, fascinated and appalled the nation for almost eight years and has, seemingly incidentally, severely damaged the Socialist Party. Yet, although some reports barely mentioned the fact, The Independent was scrupulous enough to acknowledge that the arguments about the case are far from over.

While noting that Silvino himself had pleaded guilty, it reported that the best known of the defendants, the celebrated television presenter Carlos Cruz, once known in Portugal as ‘Mr Television’, had dismissed the verdict and vowed to fight on. According to Cruz: ‘This is one of the most monstrous judicial mistakes in Portuguese history.’

Carlos Cruz at the end of the trial, September 2010

The other four high-profile defendants who were convicted have also protested their innocence throughout the trial and they, like Cruz, have launched appeals. All of them have already spent time in prison but the trial went on so long that the legal-limit for pre-trial custody expired. They are currently still free, because in Portugal a prison sentence is automatically suspended when a defendant appeals.

Most people who observe the Casa Pia case from a distance will dismiss the moves to appeal as routine. But there are many reasons why Cruz’s denials, (which he has set out on a website launched in June 2010 — www.processocarloscruz.com), and the protestations of innocence made by his fellow defendants, should be taken very seriously indeed.

The Comedian and the Politician

One of the main grounds for saying this is that the convictions which have been obtained in the case rest on foundations which, as the court itself has acknowledged, are without any material basis. Instead of offering solid evidence that crimes have been committed, the court has made the assumption that one allegation is capable of corroborating another. A crucial role has also been played by the testimony of the trial’s central figure, Carlos Silvino.

By all accounts Silvino is guilty of a significant number of the 630 offences he was charged with. But at first when he was arrested he repeatedly denied the suggestions which were put to him that he had been part of a paedophile ring. Only after changing his legal team a number of times and taking on as his fifth lawyer José Maria Martins, a former policeman, was he persuaded to ‘co-operate’ with the police and to help build the case against the other defendants.

By this point even the prosecution had dropped the claim that there had been an organised paedophile ring and replaced this by the notion of an ‘informal group’. The advantage of this from the point of view of the prosecution is that, whereas membership of a paedophile ring would indicate a criminal conspiracy, which would need proof to substantiate it, the existence of an ‘informal group’ had no legal implications and could be assumed without evidence. The paedophile ring narrative which had been created at the outset of the investigation was thus abandoned by the prosecuting authorities while being continued by by journalists.

Some supporting evidence was still needed, however. From the transcripts of the trial which have been reported in the Portuguese press it is quite clear that Silvino was led to believe that if he pleaded guilty to all the counts against him and agreed to testify against his fellow defendants, he would benefit. He would receive a reduced sentence of four or five years (or even a suspended sentence) instead of the twenty-five years the police were threatening him with.

This kind of plea bargain is illegal in Portugal. This may be why, in the event, Silvino, was sentenced to eighteen years. The fact that he was denied the leniency he had been promised, however, should not be allowed to obscure the role he played in securing the conviction of his fellow defendants.

The quality of the allegations which Silvino had been asked to ‘corroborate’ may be judged from what happened to three people who nearly found themselves standing trial alongside these defendants.

Among the public figures who faced allegations relating to Casa Pia in 2003 were Paulo Pedroso, a highly regarded socialist politician and former employment minister, Francisco Alves, a celebrated underwater explorer, and a well-known TV comedian, Herman José.

Comedian Herman José

The case of Herman José is perhaps the most telling. Having been accused of various offences of child sexual abuse connected with the Casa Pia homes, he was summoned to appear in court in May 2003, charged with sexually abusing a teenager. In the event, however, he was able to show that, at the time in question, he had been recording a television programme in Brazil. He had apparently been selected as an alleged perpetrator because he was well-known. Faced with this evidence, the judge, Ana Teixeira e Silva, dismissed the allegation.

The case of Paulo Pedroso, once regarded as a future leader of the Socialist Party, followed a similar course. It was eventually established that he had been named by his first accuser only after the young man in question had been shown an ‘album’ containing photographs of some eighty men. Pedroso’s photo was featured alongside those of a number of other politicians. The name Paulo Pedroso had, in effect, been produced by the alleged ‘victim’ in response to a multiple choice test. Only when the investigators had themselves successfully created a template for this allegation, did other former residents of Casa Pia make their accusations against Pedroso.

Former employment minister Paulo Pedroso

In May 2004, when the evidence against Pedroso was examined, the case against him was dropped. The same thing happened with Francisco Alves. However this was not the end of the affair for Pedroso, who spent four months in custody and whose political career was destroyed. In 2005, during the trial, Carlos Silvino (or ‘Bibi’) was giving evidence about an occasion when he claimed that he had ferried a number of teenagers to sex parties at the home of one of the defendants. He claimed that Pedroso had been present at these parties.

Shifting the evidence

These claims were based on statements which had been made during the investigatory phase of the case and lawyers acting for Pedroso now made a complaint of defamation against the authors of these statements. But it was one of the lawyers acting for the alleged victims who made the most revealing comment. António Pinto Pereira criticised the decision not to indict Pedroso. ‘There can be no room for doubt — Paulo Pedroso must be brought to trial,’ he said. ‘The same evidence that led to the indictment of other defendants has led to his [Pedroso’s] non-indictment.’ In this respect Pereira was quite right. The young men who accused Pedroso were exactly the same as those who accused Carlos Cruz; they even cited the same place and the same times.

What Pereira seems not to have understood is that his analysis cuts, or ought to cut, both ways. For what the incident appeared to suggest was that the evidence on which the Casa Pia defendants had been forced to stand trial over a six-year period might be no more reliable than the evidence in the cases which had been (rightly) dismissed.

If any doubts about this remained, they should have been finally removed by one of the most extraordinary developments which took place towards the end of the Casa Pia trial. Bizarre though it was, this development remains completely unreported in the accounts of the trial which have appeared in the English-speaking press.

What happened is that, through diligent research carried out by their legal teams, the defendants were able to demonstrate that, in a number of instances, they could not have been where the alleged offences supposedly took place at the times that were specified. In one case the doctor’s surgery where abuse was said to have taken place had not even been built. According to any reasonable court of law this would have meant that the case against the accused would collapse. However, in an attempt to secure the convictions of the various defendants, the prosecution submitted a formal request to the presiding judges. They asked for more than 40 changes of date, time or place to be made to the indictment.

This request was opposed by the defendants’ legal teams but, their protests notwithstanding, the judges eventually permitted no fewer than 11 of the changes. This gave the accused no time to defend themselves against the substantially different allegations they now faced. Carlos Cruz’s lawyer, Ricardo Sá Fernandes, said during his closing speech to the court that the decision to ratify these changes had brought with it ‘the greatest disillusion’ in his professional life. ‘To me this decision is incomprehensible and could only be the product of prejudice’, he said.

These were the circumstances in which the three judges, who appealed in their judgment to the ‘emotional resonance’ (p. 1,223) of the allegations which had been made, and to the ‘resonance of truth’ (p. 978), which had emerged during the trial, found the five high-profile defendants guilty.

Myths and Fantasies

In any attempt to understand what has happened in Portugal over the last six years, it is important to place the scandal in a larger perspective.

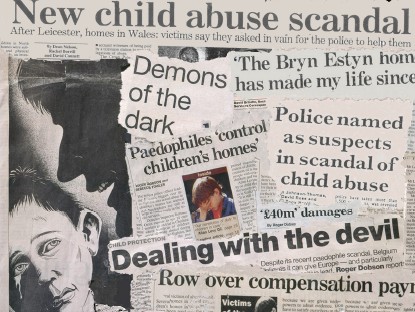

As I wrote in my first article about the Casa Pia scandal seven years ago, the idea that there is a paedophile ring centred on a children’s home, which supposedly supplied young boys to prominent figures and politicians, is one which seems to have originated in Britain. It first surfaced in 1980 in relation to the Kincora working boys’ hostel in East Belfast. It then reappeared in 1991 and formed a significant strand of the Bryn Estyn scandal which would eventually lead to the North Wales Tribunal. In 2008 a similar story became the basis of the Haut de la Garenne children’s home scandal in Jersey.

In all three cases the so-called ‘children’s homes’ turned out in reality to cater mainly for adolescent boys, some of whom (in the case of Bryn Estyn) had criminal records. The allegations which emerged were not made by children but were collected retrospectively from young adults.

In all of the cases there was a core of reality to the stories which emerged; at Kincora, at Bryn Estyn and at Haut de la Garenne, a few young teenage boys were sexually abused by one or two members of staff. But this reality was then overlaid by the fantasy that large numbers of innocent young people had been preyed upon by an evil conspiracy.

In the Bryn Estyn scandal in North Wales this fantasy rapidly became the basis for a righteous crusade to convict the alleged perpetrators. Journalists in particular were prominent in driving the crusade forwards. Whenever investigations concluded that such ideas were groundless, the authorities were accused of engaging in a cover-up. In order to make these accusations credible it was claimed that politicians themselves, or even police officers, were a part of the ‘ring’ they were supposed to be investigating and therefore had an interest in concealing its existence. Similar claims were made frequently during the series of satanic abuse cases which began in California and swept through North America and Britain during the closing decades of the twentieth century.

Bryn Estyn and the North Wales scandal: newspaper headlines

Gripped by this kind of righteous fantasy, journalists, social workers and police officers tend to discount any evidence which seems to point to the innocence of those who are accused. Such evidence will be rejected, disbelieved, or sometimes quite deliberately concealed. At the same time investigators or prosecutors who join in this kind of purity crusade will tend to tolerate any method of investigation, however dangerous or unsound, so long as it produces evidence of wrongdoing.

In the Bryn Estyn scandal police officers actively sought out former residents of the home, who were often street-wise young men with long records of dishonesty. By asking leading questions in circumstances where it was well-known that large amounts of compensation would be available to those who made allegations of sexual abuse, they were doing something which was intrinsically dangerous. This was recognised by the Canadian judge, Fred Kaufman, when he investigated the spate of compensation-fuelled false allegations made in Nova Scotia in the 1990s. As he wrote in his report: ‘Sexual abuse claimants should not be regarded as immune from the temptations and incentives — particularly monetary — that move human beings generally, just because they allege sexual abuse.’

What the environment of compensation meant in practice is that police officers in North Wales were able to ‘create’ the evidence they were seeking.

In North Wales the idea that politicians were part of the paedophile rings which had supposedly infiltrated children’s homes never got beyond the stage of malicious rumour. But, in the case of Bryn Estyn, this did not stop the moral panic from developing. The scandal rapidly spread across the Welsh border to police forces in neighbouring Cheshire and Merseyside and from there to the rest of England. Between 1990 and 2000, police trawling operations collected literally thousands of allegations from former residents of UK care homes. As I have argued in The Secret of Bryn Estyn: The Making of a Modern Witch Hunt, and also before a House of Commons Select Committee, all the evidence suggests that as many as 80 to 90% of the serious sexual allegations collected as a result were false.

The mass production of such evidence, however, creates a particular kind of vicious circle. This is because, the more publicity any alleged crime attracts, the stronger become the pressures to obtain convictions — and to obtain them at almost any cost. In cases involving alleged paedophile conspiracies there is an added pressure. For investigators and prosecutors to fail to convict in such cases is to risk the claim that they have become a part of the conspiracy they are supposed to be exposing — that they are paedophiles themselves.

Crossing The Line

So powerful and so psychologically compelling do the pressures to maintain righteousness become that, at a certain extreme, it is common for investigators or journalists or both to ‘cross the line’. What happens is that the integrity of the normal investigative process is destroyed and replaced by the rules of the witch-hunt. Journalists and investigators will then actively misreport or misrepresent the true facts, or even fabricate evidence which points towards the guilt of the accused.

Chris Lillie and Dawn Reed

One of the British cases in which this happened was the Shieldfield nursery case in which two young nursery nurses, Dawn Reed and Chris Lillie, were falsely accused of belonging to a non-existent paedophile ring.

When Reed and Lillie were found not guilty in a criminal trial in 1994 a riot took place in the courtroom led by parents who believed they were paedophiles. In response Newcastle City Council set up an ‘independent panel’ of four social work experts who, in a report published in 1998, found the two nursery nurses guilty over the heads of the court. At one stage it was claimed that Reed and Lillie had sexually abused as many as 350 young children.

Because of the lynch-mob response to this report whipped up by the press, Reed and Lillie went into hiding in fear for their lives. At this point the journalist Bob Woffinden and I decided that we would find them. We did so and then spent many months analysing the evidence in the case. Having established that this pointed to the innocence of Lillie and Reed, we found lawyers who would take the case on.

As a result, the findings of the independent panel and of the paediatrician who examined the alleged child victims were scrutinised by the High Court during a six-month libel trial, in which the two nursery nurses successfully established their innocence.

Under cross-examination, the paediatrician in the case, Dr Camille Lazaro, actually admitted that her reports on behalf of supposedly abused children to the Criminal Injuries Compensation Board were ‘overstated and exaggerated’. Other elements of her evidence, and of the report compiled by ‘independent panel’, were found by the court to have been misleading, dishonest or untruthful. As I wrote at the time:

Again and again the end had been used to justify the means and what has been called ‘noble cause corruption’ had triumphed – or would have triumphed but for the libel trial.

If it is the case that the more noble the cause, the more likely it is to engender dishonesty and deception on the part of normally honest citizens, then allegations of child sexual abuse may be particularly prone to lead to just the kind of untruthfulness which was repeatedly exposed in the trial.

Outreau: a judge’s zeal

In the climate of fear which has been created around child sexual abuse and paedophiles, witch-hunts similar to that which was unleashed against Dawn Reed and Chris Lillie have already taken place in many countries. A moral panic which had its origins in California in the 1970s and 1980s, had, by the 1990s, spread to many parts of the English-speaking world. It had also spread to Scandinavia and to parts of Europe.

One of the most notorious of the European cases took place in Outreau in northern France some five years ago. It was here that Fabrice Burgaud, a young judge, found himself investigating a case of sexual abuse within a family. He soon convinced himself that he had stumbled on a wide-ranging paedophile ring. Responding to his prosecutorial zeal, the two people at the centre of the case began accusing neighbours in order to spread their own guilt. They later admitted that the judge himself had suggested the names they had ‘spontaneously’ denounced.

Fabrice Burgaud at a parliamentary hearing, 2006

Driven by his mistaken belief that he had uncovered a paedophile conspiracy, Burgaud detained 13 people in custody, most of them for three years. But seven were acquitted at a trial in St Omer in 2004 and the remaining six had their convictions overturned at appeal in 2005. During this time parents were separated from their children and one of the defendants committed suicide. In an unprecedented letter of apology to the defendants, President Chirac described the affair as an ‘disaster’, and promised judicial reform.

Outreau is merely one of the most disturbing in a wave of literally hundreds of cases based on non-existent paedophile rings. Those who have studied the Casa Pia scandal most closely, in particular the Portuguese investigative journalist Jorge Van Krieken, are in no doubt that this wave of moral panic has now reached Portugal.

If Van Krieken’s analysis of the case is proved right, it may well be that the Casa Pia case in Portugal will eventually become what the Outreau case was to France. It may become, in short, a case which prompts calls for the radical reform of an entire judicial system.

Reporter X

Jorge Van Krieken, whose researches were, until 2007, documented on his website, ReporterX.net, is a dissenting freelance journalist who values his independence above all else and has published many articles about the Casa Pia scandal.

In 2004 he published an article in 24 Horas about what is perhaps the most shocking aspect of the entire case — the role played by the ‘album’ of photos which had been used by the police as a means of gathering allegations. It transpired that the same album which had been used to seek allegations against Paulo Pedroso had been used against all the defendants who are currently standing trial. The first edition of the album, compiled at the outset of the case, contained photographs of some 30 different people. The second edition had photos of 84 people, and the third edition contained 127 people, whose names were eventually made public.

In order to render it ‘fair’, the album supposedly included the photos of non-suspects as well as suspects. The alleged victims identified the men they said had abused them by picking from photos which included the Portuguese president, Jorge Sampaio, Cardinal Patriarch José Policarpo, the socialist leader Ferro Rodrigues, the footballer Eusebio, artists, entertainers and a host of other figures including Paulo Pedroso, Herman José and all of the five high-profile defendants who were recently convicted.

Most disturbingly of all, the album also included journalists who had been critical of the investigation. When he studied the list of those featured in its third edition, Van Krieken discovered that he appeared as number 98. He still counts himself fortunate that, perhaps because his photo was a late addition to the gallery, he did not himself become a victim of false allegations.

What the final edition of the album clearly demonstrated, however, is that Van Krieken had already become a marked man. In February 2006 he became the focus of national attention once again when one of his stories led to a police raid and the confiscation of his computer.

Click image for video clip featuring Jorge Van Krieken

In November 2006 he gave evidence to the Casa Pia trial on behalf of the defence. During his testimony he made it quite clear that he was not seeking to place new facts before the court. Rather he was offering a fresh analysis of evidence which was already in their possession. This was misreported in some newspapers by journalists who were hostile to his views as an admission that he had no new evidence, and therefore as a victory for the prosecution.

Although Van Krieken’s actual aim was to defend innocent people who had been wrongly accused, he was reviled by bloggers and others as somebody who had produced ‘tons of garbage’, and who was intent on ‘persecuting the victims of the paedophiles and discrediting the investigation’.

In fact Van Krieken’s understanding of the Casa Pia case rests in part on his analysis of the computer databases and phone logs on which the Casa Pia prosecution was based. Having obtained leaked copies of these, he spent hundreds of hours analysing this data. He eventually submitted this analysis, recorded on a number of CDs containing tens of thousand of pages of data, to the trial judges after he had finished giving evidence.

His overall conclusion is that the Casa Pia case was, like some of the British cases, based on a core of reality. There is clear evidence that adolescents or young men who were resident at Casa Pia had themselves made money by acting as male prostitutes and selling their services to clients outside the homes. Carlos Silvino appears to have had some involvement in this kind of trade and was guilty of exploiting and abusing residents for his own gratification.

There was also a slender thread which linked Jorge Ritto, the former ambassador and a discrete homosexual, to the Casa Pia homes. In 1982, two young people who had run away from Casa Pia were found in Ritto’s appartment at a time when he was away. A prosecution of Ritto was launched but dropped for lack of evidence. During the investigation, one Casa Pia resident made a claim, later retracted as an invention, that Carlos Cruz was a frequent visitor to Ritto’s flat.

More than fifteen years later these facts were dug out and presented in court. The records of millions of phone-calls were then produced in an attempt to demonstrate links between the defendants and the alleged victims.

Creating Allegations

After studying in detail the evidence which emerged in the trial, Van Krieken has come to the conclusion that the entire prosecution case is unsupported by any substantive evidence. What has happened, in his view, is that the prostitution which was undoubtedly taking place in relation to some of the Casa Pia homes provided the ideal setting in which to ‘create’ evidence for a fantasy: that vulnerable young children were being preyed on by an organised paedophile ring whose members were drawn from the elite.

As in the Bryn Estyn case, so in the Casa Pia case, Van Krieken believes, journalists became gripped by this idea at the very outset. By manufacturing a paedophile ring for which there was no evidence, they effectively created a need to find and incriminate celebrity suspects. Police officers then responded by actively seeking out ‘victims’ who would testify against these suspects.

Inadvertently the investigators created a template for the allegations they were seeking. By asking leading questions and by showing their album of photographs to potential victims, they effectively sowed the seeds of the allegations they subsequently harvested.

The prospect of compensation was also a crucial factor. Van Krieken says that, as soon as they were approached during the investigation, former residents of Casa Pia were required to sign a form which confirmed their entitlement to compensation. Partly because of this and partly because many of the ex-residents in question were vulnerable adults, some of whom were dependent on drugs, large numbers of false allegations were rapidly collected.

Van Krieken believes that the manner in which the evidence in the case has been contaminated is — or at least should have been — apparent in the documents which were before the court. During the trial he pointed out that the prosecution had commissioned a detailed forensic analysis of the phone-calls which were originally supposed to lie at the heart of the prosecution case. However, the report containing the conclusions of this analysis had disappeared. It formed no part of the documentation which the court considered.

Having conducted his own exhaustive computer analysis of the phone log in question Van Krieken believes he knows the reason for this. He claims that any thorough analysis points not to the guilt of those who have been accused but to their innocence. He believes that this finding was withheld by the prosecuting authorities in order to ensure that the defendants were convicted.

When, as a result of Krieken’s investigations, the existence of the report was eventually acknowledged, the prosecuting magistrate João Guerra attempted to explain its absence from the trial by saying that it was ‘non-probative’ [não prova]. Van Krieken rejects this, insisting that the rules of disclosure were broken and that the report should have been placed before the court precisely because it undermined the entire basis of the prosecution case.

In short, he has come to the conclusion that the same kind of ‘noble cause corruption’ which took place in Britain in the Shieldfield case can be found at the heart of the Casa Pia trial. So intent had the prosecution become on securing the conviction of the defendants that at times they had been driven to ignore the very rules which were designed to ensure that trials are fair and that innocent people are not convicted. Speaking to me in English, Van Krieken says ‘If you commit crimes in the name of justice, that is the worst that can happen to us.’

When I ask Van Krieken whether he believes that not only Carlos Cruz, but the other four defendants who were convicted with him are actually innocent, he does not hesitate. So far as the charges which are before the court are concerned, he says, there is no credible evidence to connect any of the five high-profile defendants with any of the alleged victims. In Van Krieken’s view the evidence suggests, in short, that the Casa Pia five are indeed innocent of all the allegations made against them during the trial.

The implications of these claims, if they are true, are massive. The most important question which arises from them is a simple one. If the prosecution of the five men who now protest their innocence is entirely without substance, why did the scandal develop in the manner that it has?

It is this question, I believe, which can and should now be answered.

http://www.richardwebster.net/casa-pia-carlos-cruz-reporterX.html

…………………………………………